- Blake Snyder Beat Sheet Example

- Blake Snyder Beat Sheet For Writing Books

- Blake Snyder Beat Sheet High Resolution

- Blake Snyder Beat Sheet For Writing Books

- Blake Snyder Beat Sheet Famous Movies

- Blake Snyder wrote an influential plotting guide, Save The Cat, which contains his famous Beat Sheet. Tim Stout, himself a writer of a how-to guide on writing graphic novels, has put a condensed version of the Beat Sheet up on his blog, and I’m going to quote the whole thing.

- 'The Beat Sheet calculator allows you to enter the total projected number of pages in your screenplay, and then returns to you a beat by beat sheet of the fifteen major events in the Blake Snyder Beat Sheet.'

- Blake Snyder's Save the Cat is a classic among screenwriters, but all storytellers, including novelists, will find valuable gems of insight in it. Get Started; Tools. Novel Beat Sheet. Marilyn Brant, September 3, 2020 17 min read. The Save the Cat!® Storytelling Webinar Is.

In his best-selling book, Save the Cat!® Goes to the Movies, Blake Snyder provided 50 “beat sheets” to 50 films, mostly studio-made. Now his student, screenwriter and novelist Salva Rubio, applies Blake’s principles to 50 independent, auteur, European and cult films (again with 5 beat sheets for each of Blake’s 10 genres).

Blake Snyder Beat Sheet Example

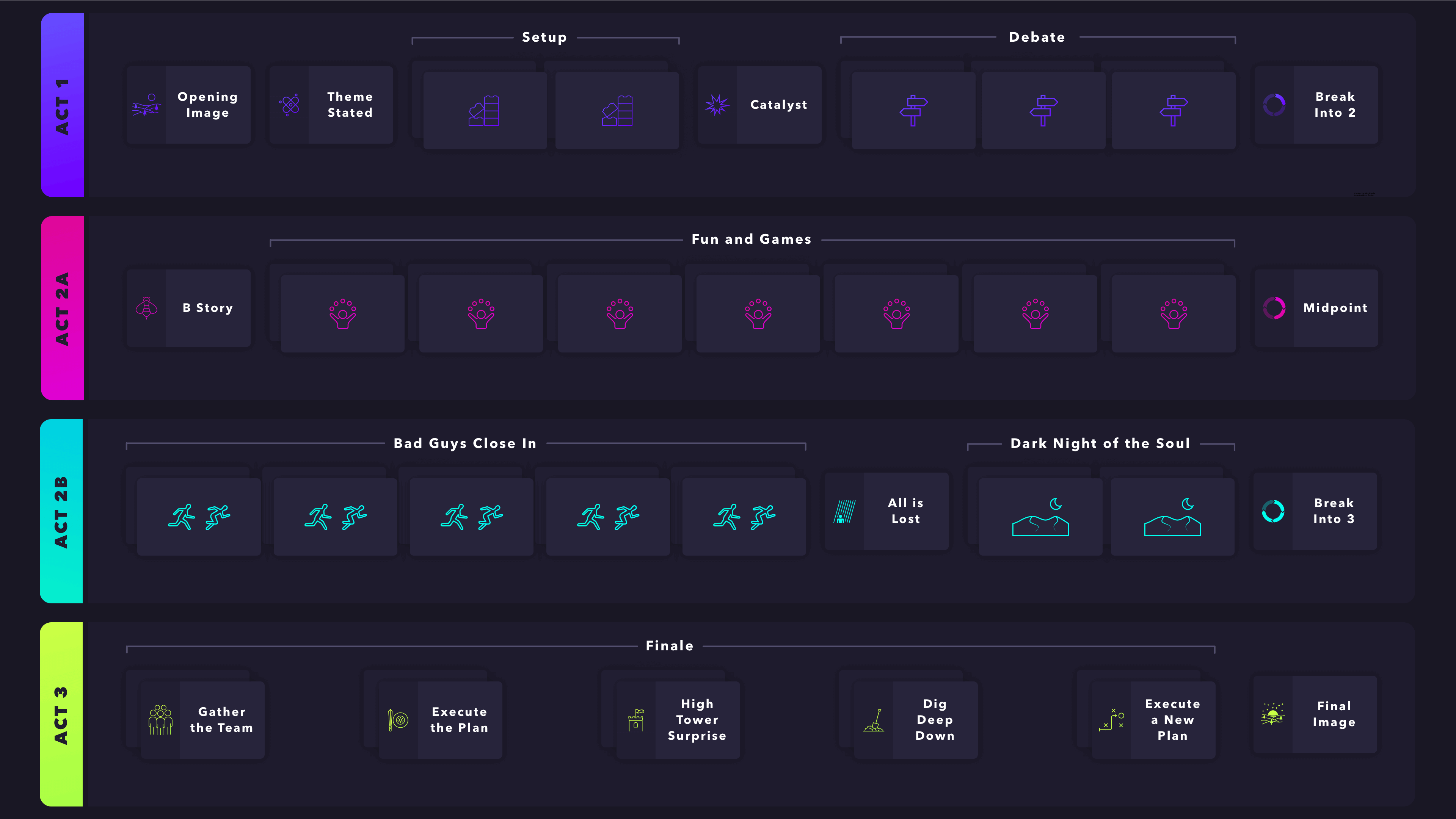

Blake Snyder’s beat sheet from Save the Cat! The Last Book on Screenwriting You'll Ever Need is the primary structure or foundation by which we are going to build our story. It’s the skeleton of the screenplay on which we will soon put on flesh. The beat sheet is a lot more than just Act I, Act II and Act III.

Snyder offers 15 different “beats” that writers of a screenplay should be cognizant to include in the storyline. The numbers next to each of these beats represents approximately on which page or page range they should occur (given that each page of a screenplay is typically about one minute of screen time).

By the way, assembling your beat sheet is the fourth stage that Snyder reccomends when preparing your screenplay. If you're interested in reading about the other stages in a screenplay, check out my 8-Step Guide to Writing Great Screenplays.

The Beats of a Screenplay

Opening Image (Page 1): This is the first impression of the movie: tone, mood, colors, type, scope, genre, the frame universe of the story.

Theme Stated (Page 5): Someone poses a question or makes a statement that reveals theme, but make it a passing offhand comment. Should not be “on the nose” or “too obvious.”

Set-up (Pages 1-10): This is the “make or break” section where you must grab audience or else lose them altogether.

Catalyst (Page 12): This beat can also be called the inciting incident or new opportunity. It is the moment that sets the rest of the film into motion.

Debate (Pages 12-25): The debate gives the hero the chance to say “should I really do this?” and shows how the hero could possibly answer the question or solve the problem, which leads to a firm decision to…

Break into Act II (Page 25): In Act II we leave the old world (the thesis) and journey into the upside down new world (antithesis).

B-story (Page 30): The love interest of the story may have already been introduced but now it becomes obvious there will be a relational connection with the hero.

Fun and Games (Pages 30-55): The Fun and Games beat is the promise of the premise: where most of the trailer’s moments are found and the focal point of the poster. Here we take a break from the high stakes and are more concerned with having some fun.

Midpoint (Page 55): At the midpoint you'll want to create an obvious “up” tick (hero seemingly peaks…but not really ) or a “down” turn (world begins to collapse around the hero…but not really).

Bad Guys Close In (Pages 55-75): It is during this beat that the hero appears to have nowhere to go for help, headed for a huge fall, which leads us to…

All is Lost (Page 75): This is the point of the script where the hero experiences a false defeat: hero is in shambles, wreckage everywhere, no hope: where mentors die and best friends betray.

Dark Night of the Soul (Pages 75-85): This section can last five seconds or 10 minutes. This is where the hero reacts and processes the defeat and when the hero reaches down deeper than ever before to find the strength/wisdom needed to overcome the conflict.

Break into Act III (Page 85): In Act III our hero discovers the solution. Both the external A-story and internal B-story meet and intertwine. The hero gets the clue from the girl that makes him realize how to beat the bad guys and eventually win the girl’s heart (“whew”).

Blake Snyder Beat Sheet For Writing Books

Finale (Pages 85-110): The finale is compromised of the big sequences of the entire film: the payoff moment where hero shines; problem is solved, bad guys are killed/defeated, and of course the hero wins the girl. This beat has lots of action and important dialogue. Remember to tie up any loose ends in this beat as most of puzzle’s solutions are now revealed to the audience.

Final Image (Page 110): This is the opposite image of the opening image; proof that change has occurred and that it’s real.

What do you think about this? What beat would one of your favorite movie scenes fall under? Let us know your answers in the comment section below.

Want more ThoughtHub content?

Join the 3000+ people who receive our newsletter.

Learn more about writing screenplays

*ThoughtHub is provided by SAGU, a private Christian university offering more than 60 Christ-centered academic programs - associates, bachelor's and master's and doctorate degrees in liberal arts and bible and church ministries.

Have you heard of Blake Snyder? He was a screenwriter and writer of several terrific books about screenwriting (tragically he died in 2009 at fifty-one) includingSaveThe Cat! (23 printings so far) and Save the Cat Goes To The Movies. Highly recommended.

Blake Snyder was famous for his “beat sheet.” This was his original, funny, idiosyncratic (and very insightful) way of breaking down a story into its constituent elements. There are fifteen beats in the Blake Snyder beat sheet, starting with “Opening Image” and continuing through “Set-up,” “Catalyst,” “B Story,” “Bad Guys Close In,” “Dark Night of the Soul,” etc.

Number Eight is “Fun and Games.”

Here [writes Blake] we forget plot and enjoy “set pieces” and “trailer moments” and revel in the “promise of the premise.”

The Fun and Games part of the story, according to Blake Snyder, begins around the start of Act Two in a movie (for books, say simply “the middle”) and can continue most of the way to Act Three.

What exactly are Fun and Games?

They’re what we go to a specific movie (or read a specific book) for.

We go to a Terminator movie to see Arnold Schwarzenegger destroy things. We go to a Hitchcock flick for the scares and the Icy Blonde in Jeopardy scenes. We read Philip Roth for upscale Jewish angst (and sex) and we pick up Malcolm Gladwell for quirky but profound insights into common but often-overlooked phenomena.

Blake Snyder Beat Sheet High Resolution

The Fun and Games of a historical romance are the bodice-ripping love scenes. The Fun and Games of a musical are the songs. The Fun and Games of a French restaurant are the gorgeous veggies, the meats and fish roasted with pounds of butter, and the impeccable complementary wines.

A case could be made that the plot of any novel or drama or epic saga, back as far as Beowulf and the Iliad, is nothing grander than a vehicle to deliver the Fun and Games.

And that the writer’s first job, before the application of any and all literary pretensions, is simply to make the Fun and Games work.

Consider Begin Again, the Keira Knightley-Mark Ruffalo-Adam Levine movie I was talking about in a post a couple of weeks ago. Begin Again is (more or less) a musical. The Fun and Games are the songs. Writer-director John Carney had, I don’t know, eight or ten tunes that he had to weave into the story. I’d be very surprised if he didn’t sit down with a notebook and ask himself:

1. How am I going to work each of these songs into the film?

2. Which characters sing them? And why?

3. How can I make each song serve and advance the story?

4. How can I make each song serve the story differently from every other?

5. In what order do I put the songs?

In other words, John Carney began with the Fun and Games. His task was to make them work in the story.

I gotta say, he did a tremendous job. For one song he had Keira Knightley, sitting alone at night in a New York apartment, open her laptop and watch a private video of herself singing for Adam Levine (her boyfriend in the movie) a song she had just written, asking him if he liked it, if he thought it was a good song. Tone of scene: wistful, romantic. Message: she loves him.

In another scene, Carney had Adam Levine play back a song for Keira on his iPhone (a song he had just written during a week out of town.) Twist: Keira realizes as she’s listening to the song that Adam wrote it for another girl. Upshot: she slaps his face and bolts.

What made the task of integrating these Fun and Games particularly daunting for John Carney was that only one or two of the songs had lyrics that referred overtly to what was happening in the moment in the story. They weren’t like “Willkommen” or “What I Did For Love.” They were just generic love songs, like you’d find on any album.

Why am I bringing all this up? I’m flashing back to last week’s post, Learning the Craft. In that post I suggested that it would be a tremendously helpful exercise for all of us to ask ourselves, “What is our craft? What are our strengths as writers? What is unique to us stylistically, thematically, dramatically?”

Same for Fun and Games.

What are our Fun and Games? Even if we’re as-yet unpublished. Even if we’ve only written one story, or just part of a story. What would a reader pick up our book for? What boring parts would she page through to get to the “good parts?”

What are our “good parts?”

The reason I suggest his exercise is because most of us have no idea what our Fun and Games are. I didn’t for years.

If someone were plunking down money to buy a book by you, what would they be buying it to get? What scenes or moments would they want to see? A certain kind of love scene? A trademark type of action or suspense? Are they licking their chops to read your brilliant excursus on American foreign policy? Are they seeking your insights on the evolution of women’s political consciousness in the 1970s?

It’s tremendously helpful to know the answers, to know what our Fun and Games are, because:

1. They tell us what our strengths are.

2. They identify what’s fun for us, what types of scenes we gravitate to.

3. They provide insight into what themes preoccupy us. (Our Fun and Games will instinctively support our themes, consciously or unconsciously.)

4. They help us answer the question, “Why do we write?”

5. They give us insight into who we are, long-term, in the sense of our evolving journey as artists and as human beings.

6. And they help us understand what issues are preoccupying us now, today, in this immediate moment of our lives.

Blake Snyder Beat Sheet For Writing Books

What are your “trailer moments?” What are your “set-pieces?”

What are your Fun and Games?

Blake Snyder Beat Sheet Famous Movies

[P.S. Check out Blake Snyder. Well worth reading.]